How COVID-19 Changed High Schools in One Year

When schools shut down in March 2020, no one knew how long it would last. By the end of that school year, over 99% of U.S. high schools had closed their doors. What followed wasn’t just a pause-it was a complete rewrite of what high school even meant.

Classrooms vanished overnight

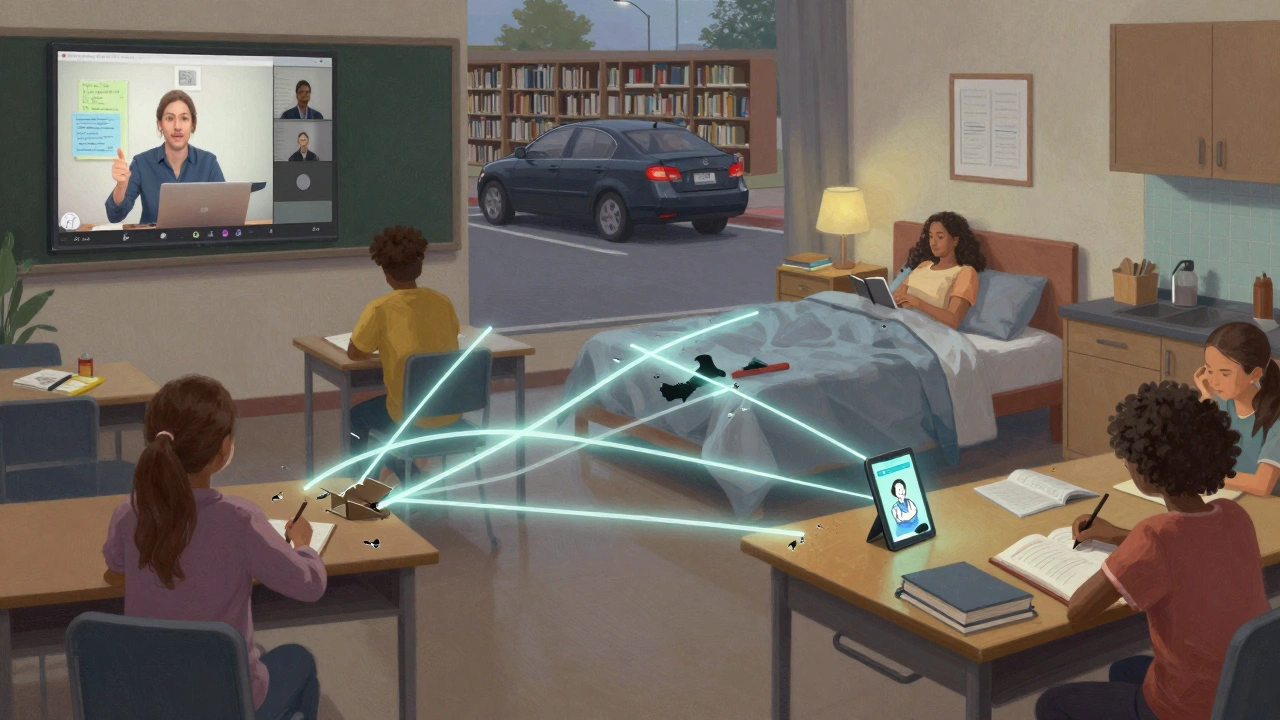

One Monday, students walked into hallways buzzing with locker slams and lunchroom chatter. The next, they logged into Zoom from their bedrooms. Teachers scrambled to turn lesson plans into digital packets. Some districts handed out Chromebooks like they were textbooks. Others relied on paper packets mailed to homes without reliable internet.

In Asheville, a senior named Jamal got his first laptop two weeks after school closed. He did his final exams on his phone while sitting on the porch because the Wi-Fi signal was stronger there than inside his apartment. His math teacher recorded video lessons on her phone and uploaded them to YouTube. By April, half the class hadn’t turned in a single assignment. Attendance wasn’t tracked anymore-it was impossible.

Grades became a gamble

Grading systems collapsed. Some schools switched to pass/fail. Others let students opt out of final exams. A survey from the National Association of Secondary School Principals found that 68% of high schools changed their grading policies during the 2020-2021 school year. Many dropped letter grades entirely.

At Westfield High, students could choose between a traditional grade or a ‘satisfactory’ mark. College admissions officers didn’t know what to do. Some ignored grades from that year. Others asked for personal statements explaining academic gaps. A student in Ohio got into Yale with a 2.8 GPA because she wrote about caring for her younger siblings while her mom worked double shifts at the hospital.

The loneliness no one talked about

High school isn’t just about algebra and history. It’s about the hallway conversations before first period. The group project that turned into a friendship. The football game where everyone screams until their voices break.

When those vanished, so did the safety nets. Counselors reported a 40% spike in students asking for mental health help. Suicide prevention hotlines saw a 31% increase in calls from teens aged 14-18. A CDC study in 2021 found that 37% of high school students felt persistently sad or hopeless-up from 26% in 2019.

One junior in Texas started a Discord server just to talk. No homework. No grades. Just 20 kids sharing memes, venting about their parents, and playing online chess at midnight. It wasn’t therapy. But it kept them from falling completely apart.

Learning gaps widened-especially for the most vulnerable

Not all students lost the same things. Those with quiet rooms, stable internet, and parents who could help with algebra fared better. Students in low-income neighborhoods? Many didn’t have a computer at all. In Detroit, one school district found that 1 in 4 students had no device to learn on. In rural Georgia, kids drove 20 miles to the library parking lot just to get Wi-Fi and do homework from their cars.

Standardized test scores dropped across the board. In math, the average decline was 11 percentage points. In reading, it was 7. The gap between students in wealthy districts and those in underfunded ones grew wider than it had been in 20 years. The pandemic didn’t create inequality-it exposed it.

Teachers were drowning

Teachers didn’t get a break. They were expected to teach remotely, track attendance, respond to anxious parents, and still meet state standards-all while worrying about their own families getting sick.

One teacher in Chicago taught 150 students across five classes. She spent 60 hours a week on Zoom, grading papers at 1 a.m., and texting students who hadn’t logged in for days. She quit at the end of the year. Her district hired three replacements in six months. None lasted more than eight months.

A national survey by the RAND Corporation found that 55% of high school teachers considered leaving the profession after the 2020-2021 school year. That wasn’t burnout. That was grief.

Reopening didn’t fix everything

When schools reopened in fall 2021, it wasn’t like flipping a switch. Hallways were quieter. Lockers stayed closed. Cafeterias served meals in classrooms. Students wore masks. Some still did homework on their phones because they hadn’t gotten a laptop yet.

Attendance was still low. One school in Philadelphia saw only 62% of students show up daily. Many had fallen behind so far they didn’t know where to start. Others were afraid of getting sick. A senior in New Jersey didn’t return until February-she spent the whole year doing online classes from her grandmother’s house in Alabama.

And the learning loss? It didn’t disappear. By spring 2022, students were still averaging one full year behind in math. In some schools, teachers had to reteach 7th-grade concepts to 10th-graders.

What’s left behind

The pandemic didn’t just change how high school worked-it changed what high school meant.

Students learned that school could be done from anywhere. That teachers were human, not just authority figures. That their mental health mattered more than a GPA. Some dropped out. Others found new ways to learn-through YouTube tutorials, community college classes, or coding bootcamps.

Colleges now ask different questions. Instead of ‘What was your GPA?’, they ask, ‘What did you do when everything fell apart?’

High schools are trying to rebuild. Some added counselors. Others started ‘learning recovery’ blocks where students can catch up without pressure. But the scars remain. A generation of teens missed rites of passage: proms, graduations, senior trips. They missed the feeling of belonging.

What they didn’t lose was resilience. They learned to adapt. To teach themselves. To ask for help. That’s not just a lesson in math or science. That’s the one thing no test can measure-and the one thing that will carry them forward.

Did high school graduation rates drop during the pandemic?

Yes, but not as much as expected. The national graduation rate dipped from 85% in 2019 to 83% in 2021. That’s a small drop, but it represents nearly 200,000 fewer students walking across the stage. Many of those who didn’t graduate were from low-income families, students of color, or those with disabilities. Schools that offered flexible deadlines and one-on-one support saw much smaller drops.

Were students able to get into college after remote learning?

Yes-many did. Colleges became more flexible. SAT and ACT scores became optional at over 80% of four-year institutions. Admissions officers started looking at portfolios, personal essays, and extracurriculars done during the pandemic. Students who started YouTube channels, tutored younger siblings, or volunteered in their communities stood out more than ever. The old formula of perfect grades and test scores no longer ruled.

How did schools pay for technology during the pandemic?

Most of the funding came from federal relief packages like the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan. Schools received over $190 billion total for K-12 education. A large portion went to buying Chromebooks, Wi-Fi hotspots, and software licenses. Some districts partnered with local internet providers to offer free or discounted service to families. Still, many rural and low-income areas struggled to keep up.

Did mental health services improve after schools reopened?

Some did, but not enough. Schools that received federal mental health grants hired more counselors and started peer support groups. But the national average is still one counselor for every 385 students-far above the recommended 1:250. Many students still wait weeks for an appointment. The demand hasn’t gone down. In fact, it’s higher than ever.

Are students still behind academically in 2025?

Yes, especially in math. A 2024 study by the Brookings Institution found that high school students are still, on average, about 7 months behind in math and 4 months behind in reading. The gap is widest among students who were already struggling before the pandemic. Some schools have launched summer catch-up programs and after-school tutoring. But progress is slow. The real challenge isn’t just catching up-it’s rebuilding confidence.

What comes next

The pandemic didn’t end with a vaccine. It ended with a question: What kind of school do we want now?

Some districts are experimenting with hybrid models. Others are shortening the school day to give students time to breathe. A few are letting students earn credits through internships or community projects instead of just sitting in class.

The old system didn’t work for everyone. Maybe that’s the real lesson. High school doesn’t have to look the way it always has. It can be more flexible. More human. More ready for the next crisis.

Because there will be another one.

Nathan Jimerson

December 8, 2025 AT 23:32The resilience of students during that time still amazes me. No one handed them a roadmap, yet so many found ways to keep going-even if it meant doing homework from a porch with a weak Wi-Fi signal. That’s not just adaptability, that’s quiet heroism.

Sandy Pan

December 9, 2025 AT 19:00What we call ‘learning loss’ is really just the collapse of an institution that never truly served everyone. High school was never about equity-it was about compliance. The pandemic didn’t break it. It just showed us how hollow the structure really was. We’re not rebuilding a school. We’re deciding what kind of society we want to raise our children in.

Eric Etienne

December 9, 2025 AT 23:00Ugh. All this feels like virtue signaling. Kids got laptops, teachers got paid, colleges adapted. Everyone’s acting like it was the end of the world. I did my homework on a tablet with no Wi-Fi and survived. Stop romanticizing struggle.

Dylan Rodriquez

December 11, 2025 AT 09:38It’s not about whether the system worked-it’s about who it worked for. The students who had quiet rooms and parents who could help? They were fine. The ones who didn’t? They got left behind. And now we’re pretending we can just ‘catch up’ like it’s a missed bus. You can’t cram emotional trauma and lost belonging into a tutoring session. We need to stop treating education like a spreadsheet and start treating it like a human experience.

Some schools are finally adding mental health days. That’s a start. But we need to stop measuring success by test scores and start measuring it by whether kids feel safe, seen, and supported.

Amanda Ablan

December 12, 2025 AT 10:51I work in a high school and can confirm: the kids who came back in 2021 weren’t the same. Some were quieter. Some were angry. A few didn’t speak at all until someone sat with them at lunch and didn’t ask about grades. It wasn’t about curriculum. It was about connection. We’re still playing catch-up on that.

One girl started bringing her little brother to school every day so he could do his Zoom class in the counselor’s office. She didn’t ask for credit. She just did it. That’s the kind of stuff that matters.

Meredith Howard

December 13, 2025 AT 02:02The data shows a clear trend in academic decline especially in math but the human impact is harder to quantify

Many students lost more than instruction they lost routine identity and community

Rebuilding trust takes longer than rebuilding curricula

Yashwanth Gouravajjula

December 15, 2025 AT 00:14In India too, students learned on phones. No laptops. No internet. Just WhatsApp voice notes from teachers. We didn’t call it resilience-we just did it.

Kevin Hagerty

December 15, 2025 AT 23:42So what? Kids got soft. Now they want participation trophies for not quitting. My dad worked two jobs and still showed up to school every day. No Zoom. No excuses. Maybe if we stopped coddling them they’d grow up

Janiss McCamish

December 16, 2025 AT 14:06Eric, your comment is toxic. Kids didn’t quit because they were soft. They were drowning. Mental health crisis. Food insecurity. No internet. You think they chose this? This isn’t about laziness. It’s about survival.

Richard H

December 16, 2025 AT 19:38America’s schools are a joke. We spent billions on Chromebooks but didn’t fix the real problem-parents who don’t care. My kid’s school had a 40% absentee rate and nobody did anything. This isn’t a crisis. It’s negligence.

Ashton Strong

December 18, 2025 AT 00:55While the data reveals significant academic setbacks, I believe we must also recognize the extraordinary growth in emotional intelligence and self-direction demonstrated by students during this period. Many learned to manage their time, seek resources independently, and advocate for their needs-skills that will serve them far beyond standardized assessments.

The future of education lies not in returning to the past, but in integrating these hard-won competencies into a more humane, flexible structure.

Steven Hanton

December 18, 2025 AT 06:39I’ve seen students who didn’t speak for months after returning to school. Then one day, they started sharing stories in a quiet corner of the library. No one forced them. No one graded it. But that’s where healing began. Education isn’t just about content. It’s about creating space-for silence, for grief, for second chances.

Pamela Tanner

December 18, 2025 AT 14:49Teachers were not just teaching-they were acting as social workers, tech support, and emotional anchors. Yet most districts still pay them the same, offer the same professional development, and expect the same outcomes. That’s not just unfair. It’s unsustainable.

Until we invest in educators as human beings-not just functionaries-we’ll keep losing them. And when they leave, the students lose even more.

Kristina Kalolo

December 19, 2025 AT 14:26Did anyone track how many students learned to code or started YouTube channels during remote learning? I think the real learning happened outside the LMS